|

Mar

14

2016

|

|

Posted 9 years 359 days ago ago by Admin

|

|

I’m

going to give you a simple mental tool to keep you safe: Risk Resource

Management (RRM). It’s a tool Chesley Sullenberger used for 14 years

before he famously landed his Airbus A320 in the Hudson River. It’s also

a tool he instructed his students to use when he taught crew resource

management at US Airways. It’s a tool you can use in your helicopter to make better decisions, whether you’re flying single-pilot or multicrew.

HOW DID RRM COME ABOUT?

The

short answer is: By necessity. From 1989 through 1994 US Airways

suffered five fatal crashes in five years. The FAA gave the airline two

choices: (1) Close your doors or (2) Set up an Advanced Qualification

Program (AQP). They chose the latter.

An

AQP is defined as “a flexible training qualification and evaluation

program that permits an individual operator to design a program based on

that operator’s specific needs and requirements.” Under the AQP, the

FAA is authorized to approve significant departures from traditional

requirements, subject to justification of an equivalent or better level

of safety. For pass/fail purposes, pilots must demonstrate proficiency

in scenarios that test both technical and crew resource management

skills.

John

Ross initially developed RRM for US Airways. “If the concept wasn’t

simple I knew the pilots wouldn’t use it,” Ross observed. With that

thought in mind, he created what he calls a “make-better-decisions card”

pilots carry with them for quick reference. Ross said it was slow to

catch on but

when accepted it turned around US Airways’ terrible accident rate.

Today, because of its success, RRM has been adopted by most major

airlines.

WHAT IS RRM?

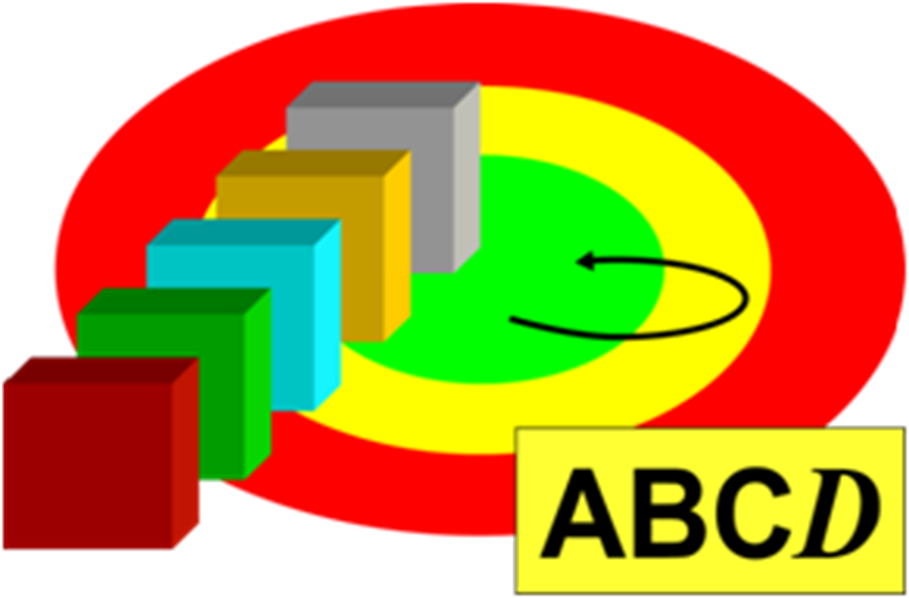

RRM

is illustrated on the card in two parts. First, think of a target. The

target is green in the middle with a yellow ring surrounding the green,

and a red ring on the outside. Think of being in the green as where you

want to be when there is no task loading. There’s no stress. If a pilot

or his crew feel they’re slipping out of this green situation with

increased tasking, thus creating potential loss of situational

awareness, their situation can slip into the yellow cautionary range,

which if unchecked could then possibly lead into the red—a true

emergency. Visualize situational awareness as gradually shrinking down

to tunnel vision with increased task loading.

Next think of the four letters ABCD: Assess the situation, Balance resources, Communicate what you see/don’t see, Do your action, then Debrief the results.

Even

though RRM had been proven to work at US Airways for years, it took two

years for pilots at Southwest Airlines (where Ross now teaches) to

fully buy in to the concept. Today 60 percent of the grading in

simulator evaluation is based on RRM. A pilot can fail a checkride if

they do not demonstrate that they have a firm grasp of— and use—RRM.

Ross explains, “What RRM does is teach pilots to say ‘No,’ thus breaking

a link in an error chain forming.”

This

mindset needs to be adopted in helicopter aviation. Think of HAI

president Matt Zucarro’s message “Land the Damn Helicopter.” The RRM

tool allows a pilot to make prudent decisions before he or she needs to “Land the Damn Helicopter.”

The

AQP evaluates human factors. At US Airways they had CRM training but

Ross wanted something beyond that. He needed a very simple process that

could be used by pilots in normal operations and during time-critical

decision-making situations. At first it was called threat and error

management (TEM), which evolved into RRM. That’s when Ross came up with

his ABCD, green/yellow/red idea.

Because

Ross’s decision-making tool was simple, it worked. There wasn’t another

major incident for 14 years, that is until Sullenberger’s aircraft hit

birds and had two engines flame out. Ross attributes the successful

outcome of that flight to the fact Sullenberger and his crew had been

trained in RRM.

THE RRM PROCESS IN MORE DETAIL

Aircrews

continually assess the color of their flights. Is it in the green,

yellow (something’s changed), or red where there is the potential for

error? Think of the RRM tool as a balancing act, where you’re striving

to remain in the green and stay on top of the situation.

ASSESS RISK: Is it green, yellow, or red? Identify present risk, potential for future risk,

and the potential for decreased performance.

BALANCE

RESOURCES: If a change has occurred, allocate resources to bring

everyone (and the situation) back into the green. Assess what tools are

at your disposal, tools such as SOPs, policies, procedures, checklists,

automation, briefings, external resources, knowledge, skills, and

techniques.

COMMUNICATE

INTENTIONS: Under stress the brain begins to shut down, creating tunnel

vision that reduces situational awareness. Communication patterns must

change when going from green to yellow to red. In the yellow,

communication has to be more direct. In the red, understanding can be

totally nonexistent. One must use very direct slow speech. You might

even have to reach over, put a hand on a shoulder and deliver your

message: “Chris, go around.”

DO the action (or perhaps do nothing at all, also a conscious decision), then DEBRIEF

the results. Were expectations met? What went well? What didn’t go

well? What can be learned for the future? Debriefing improves future

performance.

One

should recognize when you or a team member is task saturated and not

operating in the green. Know the difference between time-critical

decisions and those decisions that are not time-critical. Also

prioritize: Do the most important items first but keep flying the

aircraft. It’s important to know that RRM is not always a linear ABCD

process. Ross says it rarely is.

This

simple RRM tool: Green, Yellow, Red, and ABCD should help you make

decisions to remain in the green. Using RRM can bring you home safely,

as it did on 15 January 2009 for Captain Chesley Sullenberger, his crew …

and 155 passengers