|

Nov

30

2020

|

|

Posted 5 years 93 days ago ago by Admin

|

|

In an era when so much aviation industry news and training focuses on new technology and keeping up with so-called proficiency as proverbial boxes are checked, one often overlooked important aspect of being a pilot is being neglected—professionalism.

Recently, a colleague reached out for assistance on a new project; his company wanted to create an advisory board to offer advice on their aviation services. I was humbled he sought my advice. He garnered my full attention when he said the company was writing a quick bio on me, and then he asked me, “How long have you been flying as a professional pilot?” I had an easy and ready answer: “Since. Day. One.”

Some answers are astounding, when pilots are asked: “Are you a professional pilot?” or “What makes you a professional pilot?” Many feel once the ink is wet on their commercial pilot certificate a magic wand has been waived and they are now, by the stroke of the examiner’s pen, considered a “professional.” Likewise, many feel that once they land that first paying pilot position, they are now a professional pilot because they are getting paid to fly. This is complete and utter nonsense. You should strive to be a professional pilot on Day One! Private, commercial or ATP rated, being a professional pilot isn’t just limited to those that get a paycheck every two weeks.

To be successful in the aviation industry, or any industry for that matter, one must be a master of their environment. Mastering your environment requires professionalism throughout each step of your career. Mastering your environment will be difficult and take a lot of effort on your part. The formula itself for success isn’t difficult; don’t reinvent the wheel, instead, learn from true professionals. How do you know who the consummate professional pilots are? The answer’s clear; they often demonstrate professional characteristics. They strive for excellence, never stop learning, strive for competence, they are mentors (and have mentors), they are humble, and they are prepared. Let’s delve into each of these qualities that compose the DNA of a professional pilot.

Professionals strive for excellence. If you think the Practical Test Standards (or ACS) determine whether you are “professional” or not, you are sorely mistaken. The PTS are absolute minimums. The standards represent the lowest level of proficiency the FAA has agreed to accept. In other words, it's mediocre. For the freshly minted private or commercial pilot, I’m not downplaying your hard work as it certainly took work and effort on your part, however, don’t settle for this. You must strive to be better than a minimum standard. Don’t be mediocre; be a professional and expand on your abilities. As an examiner, on numerous occasions I’ve explained to an applicant that while they may have met the FAA’s minimum standards they didn’t necessarily meet my standards, their instructor’s, or even their own. As almost always is the case, these very applicants contact me later on in the progression of their career to tell me they pushed themselves to be better than the minimum. In other words, they strived for excellence, and sure enough these are the ones that often excel in their careers. By having this discussion with applicants, I willingly made a choice to mentor these pilots.

Professionals are mentors. One of my favorite quotes comes from Sir Isaac Newton: “If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.” Suffice it to say, the power of mentorship is priceless. As a professional pilot, you have something to offer the next generation of pilots. The aviation industry can be a real monster; tackling it alone can be challenging at best. This is where mentors come into play. Mentors create pathways for inspiration and this inspiration, when channeled correctly, can foster much success.

Consider this: mentorship works both ways. If you want to learn a lot about yourself, mentor a junior pilot just getting started. Not only have I served as a mentor to more than a couple of junior aviators finding their way in a challenging industry, but I still rely on my mentors frequently. As a professional, it is incumbent upon you to share the knowledge, wisdom, and experience you acquired. Be a giant and let junior pilots stand atop your shoulders so they can see further.

Professionals never stop learning. The role of a professional aviator is one that is constantly evolving. Changes in policies and regulations coupled with potential aircraft transitions and ever changing advancements in avionics can keep the most astute aviator chasing their tail.

Nothing is more frustrating than encountering an individual that feels they know it all, when in reality they know enough to just get by a minimum standard. While all of us need ego-strength to survive, some pilots possess an ego that often does more harm than good. This issue/personality trait has long been studied and written about in the field of psychology. It is often referred to as the Dunning-Kruger effect. The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias, one in which people (pilots) wrongly overestimate their knowledge or skill set in a particular field. This effect was first written about by Cornell University psychologist David Dunning and Justin Kruger. In their testing, Dunning and Kruger found that those who performed in the bottom quartile actually rated their skills “far above average.” The researchers determined the problem stems from a problem of metacognition, which simply put, is one’s ability to think about their thinking, or the process used to plan, monitor, and assess one’s understanding and performance. The research concluded, “Those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it.”

Today, thanks to so many technological advancements, there is little excuse for a pilot to not participate in continual learning. From numerous free or inexpensive online training programs and webinars to simply picking up a book and reviewing what you thought you already knew. The research tells us we don’t know all that we think we know. We must be better and more inclined to push ourselves to learn and to be a professional.

You must possess a knowledge toolbox. As you learn something new, a piece of knowledge or new technique, throw it in your toolbox. Having administered hundreds of FAA Certification Flight Exams ranging from the 18-year-old private pilot to the 20,000-hour pilot that finally got around to getting that ATP, I can honestly say that I learn something I am able to put into my knowledge toolbox from every single applicant. Don’t build hours; build knowledge with every flight.

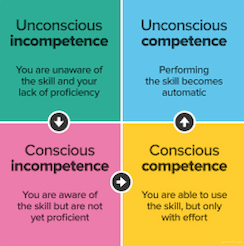

Professionals strive for competence. Competence isn’t just passing a test or passing another proficiency ride. There is a lot more to competence. In fact, competency (or lack thereof) can effectively be described and broken down into four stages. The four stages of competence dates back to the late 1960s and much if not all of the credit belongs to two men: first a management trainer, Martin M. Broadwell, who initially described the model as the “four levels of teaching,” and then in the 1970s, Noel Burch, an employee of the noted leadership training company Gordon Training International expanded the concept. During this time frame, this model was initially referred to as the four stages for learning any new skill. Today, in leadership and psychology circles it is often referred to as the “competency ladder” or most commonly as the four stages of competence, the latter of which we will discuss in this article.

As we delve into the four stages of competence, understand this; we all are somewhere, at any given time, in one of the four stages with everything. For this reason, learning the model is critical to your success. Simply being self-aware enough to know where you stand on a skill or set of skills will allow you to know exactly what you need to do to improve and master your environment.

The first stage of competence is actually anything but competence, it is the ‘unconscious incompetence’ stage (or the ignorance stage). This is where most of us start on most things in general. In this stage, we simply do not understand or know how to do something and we don’t even recognize the deficit. According to the model theory, we may even deny the usefulness of the skill entirely. In order to move on to the next stage we must recognize our own incompetence, and the value of the new skill(s).

The second stage of competence is the ‘conscious incompetence’ stage. (or the awareness stage) In this stage, even though we do not understand how to do something, we do recognize the deficit as well as the value of the new skill(s) in question. It has been said that the making of mistakes in this particular stage can be integral to the overall learning process at this stage.

The third stage of competence is the ‘conscious competence’ stage. (or the learning stage) In this stage, we understand and know how to do something, some particular skill or task. However, demonstrating the skill of explaining the knowledge behind how to do the skill often requires a heavy conscious level of thought.

The fourth and final stage of competence is the ‘unconscious competence’ stage (or mastery stage). In this stage, the one we should desire, we have had so much practice and experience with a particular skill or task that it has become second nature and can be performed easily and automatically.

Professionals are humble. Guess what? True professionals make mistakes and more importantly, the true professional learns from their mistakes. It's OK to say, "I don't know." Professionals are modest with a humbleness that fosters an increased breadth of knowledge and experience. Professionals know what they don’t know! Richard Feynman, the famous American physicist, once said, “People who pretend that they know everything and boast about their intelligence are morons - True knowledge makes people humble!” This resonating quote comes from a man who became one of the best-known scientists in the world during his lifetime. Feynman did everything from assist with the development of the atomic bomb during World War II to serve as a member of the Rogers Commission, the panel that investigated the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster in the 1980s. Feynman would end up being the person to discover the exact cause of the explosion. Feynman understood the importance of being humble, no matter one's level of intelligence or success.

Professionals are prepared. They are ready 110% of the time. I often find myself perplexed when so-called professional pilots know their Part 135 proficiency flight exams are approaching. They do everything they can at this particular time of the year to get ready and prepared for their ride. Guess what, you could very well be ‘tested’ on any given flight! You owe it to not only the passengers you fly and to your fellow citizens you fly over, but also to your family as well to be prepared 365 days out of the year, not just for one or two proficiency checks a year.

Being adequately prepared comes from training yourself to make decisions in a safe and efficient manner. I am not suggesting that one be impulsive in his or her decisions; impulsivity is one of the hazardous attitudes that we are taught to guard against. I am simply suggesting that being prepared for a ‘what-if’ can lead to better overall decisions and responses to a given set of circumstances.

So, how can one be better prepared and make more efficient decisions? It’s part cognitive science and part art. How you go about making decisions will change as you gain experience. Decisiveness will grow with each decision.

Consider this, being prepared can help you make better decisions and cut down on decision fatigue. In the field of psychology, decision fatigue refers to the deteriorating quality of decisions made by an individual after a long session of decision making. For those that study this field, decision fatigue is now understood to be one of the causes of irrational trade-offs in decision-making; something we certainly don’t need in the aircraft.

Conclusions

If you are just beginning your aviation journey I hope this article serves as a blueprint of sorts, one that will help you achieve the rewards of being a professional pilot from Day One! For those already well established in some sector of the rotorcraft industry, I hope that some or all of this article resonates with you in some way and you can throw at least one idea or tool in your toolbox.

Know where your competence level is, either seek the next level or if you are already to the desired level, then give something back! As all of us gain invaluable experience throughout our journey for success, we must make a conscious effort to mentor the next generation of pilots. Be prepared. And most importantly, stay humble.

About the Author: Matt Johnson is an FAA Designated Pilot Examiner, Part 135 Check Airman and SP-IFR Air Medical Pilot. He can be reached via email at [email protected] and via Twitter @HelicopterDPE