|

Nov

09

2020

|

|

Posted 5 years 114 days ago ago by Admin

|

|

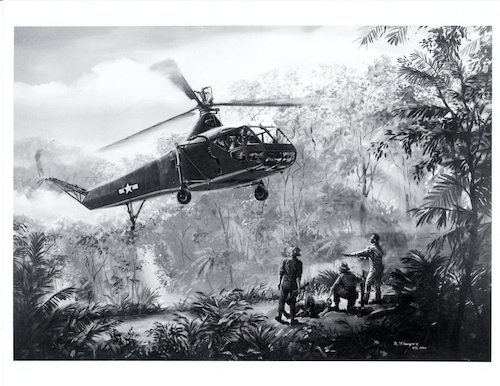

1943 was the first year that helicopters were used to perform emergency medical services (Helicopter EMS; aka HEMS). According to The Smithsonian Institution’s magazine Air & Space, it was a Sikorsky YR-4B flown by the U.S. Army in Asia that conducted the first HEMS mission in April 1944. The two-seater YR-4B flown by Carter Harman rescued three wounded U.K. Commandos and a downed pilot from the Burmese jungle, lofting one at a time to safety using four separate flights.

Since then, helicopters have become essential civilian/military ‘air ambulances.’ The road from that relatively fragile YR-4B to today’s formidable HEMS machines made by Airbus, Bell, Leonardo, MD Helicopters, and Sikorsky (now part of Lockheed Martin) has not been a smooth one. It took persuasion and performance to convince skeptics that helicopters belonged in the EMS realm.

Photo credit: Igor I. Sikorsky Historical Archives, Inc. and Artist: Andy Whyte

Military Missions

The success of the YR-4B’s Burmese rescue mission was just one instance where helicopters proved their worth in World War II, the first major conflict in which rotorcraft played a role. But it wasn’t until the subsequent Korean War (1950-1953) that EMS helicopters really caught on.

“During the Korean War, the U.S. Army would regularly airlift wounded soldiers from the front lines to field hospitals,” says Denise Uhlin, a Bell segment specialist. “The most common platform was the Bell 47, which we all recognize from the TV series M*A*S*H. It was equipped with two litters — one mounted on each side of the cabin — that were open-air.”

It was the Vietnam War (1955-1975) that saw the helicopter come into its own for HEMS missions; notably the Bell UH-1 Iroquois (initially the HU-1; aka the Huey) among others. “Unlike Korea, there were no clear front lines in Vietnam,” says Uhlin. “So medevac helicopters had to offer much more range, which is something that the Huey could do thanks to its more powerful engine and bigger payload.”

Move to Civilian Sector

The creation of civilian HEMS was inspired by the success of military HEMS.

In the United States, the first civilian HEMS to be launched was Flight For Life in 1972. Based at then-named St. Anthony Central Hospital in Denver, Colorado, Flight For Life launched using a single Alouette III helicopter.

“One reason Flight for Life was started was the demand for air ambulance services from returned Vietnam War veterans,” says Flight For Life Program Director Kathleen Mayer. “These vets had become accustomed to HEMS while overseas, and they saw no reason that HEMS shouldn’t be available here at home.”

Today HEMS has become an accepted part of American life, but it wasn’t always the case. “Flight for Life wasn’t universally popular when we launched,” says Mayer. “Other Denver hospitals thought it was a scam perpetrated by St. Anthony’s to snag their patients. Our own nurses were suspicious of their HEMS colleagues who were now wearing different uniforms and leaving work at a moment’s notice. And some of our physicians saw HEMS as a boondoggle that was taking funding away from their own projects.”

A series of calamities turned the tide for Flight for Life in Colorado. “There was the 1976 Vail gondola accident in which two cars fell to the ground, killing four skiers and injuring eight,” says Mayer. “Then there was the Big Thompson Canyon flood that same year, which killed 143 people. In both cases, our helicopter was able to get in there and provide fast assistance. This performance changed people’s attitudes about Flight For Life specifically and HEMS in general.”

Following Flight For Life’s entry in the U.S. market, other HEMS providers followed suit, such as Sanford AirMed in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. “Our program started in 1977 with a fixed wing operation, in response to the high infant mortality rate on South Dakota Native-American reservations,” says Kerry Berg, Sanford AirMed’s director of operations. “In 1986, a helicopter was added and we’ve been evolving ever since.”

Other U.S. HEMS operators, such as those who now belong to Global Medical Response (GMR), were also getting underway. “Most of our air entities got their start in the mid-to-late 1980s, when vertical flight became an up-and-coming modality for responding to a critical or sick patient within the ‘Golden Hour’,” says Tom Rohlfs, GMR's vice president of air growth.

Inspiration played a big part in this process. Rohlfs’ initial employer, Med-Trans, was born as a back-of-the-napkin concept drawn up by two competing hospitals in Bismarck, North Dakota.

The napkin concept paid off. “In 1983, the first-ever EMS helicopter in North Dakota, and one of the few in the country, started operations in a Bell 206,” Rohlfs says. “Over time, more area hospitals took notice of what Med-Trans was doing with helicopters and more programs followed suit in North Dakota and Nebraska.”

Other HEMS operations had similarly humble beginnings. For example, GMR’s Air Evac Lifeteam “was formed in August 1985 with one helicopter in West Plains, Missouri, a rural community about 90 minutes from the closest Level 1 or 2 trauma center,” says Daniel Sweeza, GMR’s senior VP of operations. “Today, Air Evac Lifeteam has more than 140 air medical locations across 15 states.”

Then there’s REACH Air Medical Services, which launched in 1987 with a single Agusta A109A helicopter in Sonoma County, California. “REACH was spurred by the vision of Dr. John L. McDonald, whose passion was to bring enhanced trauma care to serve rural communities,” says Vicky Spediacci, GMR’s West Region Air COO. “He was instrumental in developing the trauma center in Sonoma County, and part of that solution was the implementation of a helicopter air ambulance program. He did so knowing the timesaving, critical care element this could bring to the community.”

In addition to the U.S., HEMS was launching up in other parts of the globe. “The world’s first permanent HEMS base was set up by ADAC Luftrettung in Munich during November 1970,” says Ralph Setz, Airbus Helicopters’ senior manager of operational marketing for HEMS. “It was equipped with a BO105, whose flat floor, rear loading doors, and high main/tail rotors made this helicopter ideal for HEMS missions.”

Lack of space prevents us from covering all of the HEMS operations that are now in operation worldwide. Suffice it to say, HEMS is a global concept.

Advances Make a Difference

The state of HEMS has advanced considerably since 1943. Back then, the YR-4B’s rotor blades were made of laminated wood pieces. The Sikorsky factory resisted the idea of sending this helicopter to Burma, for fear that the glue holding the rotor blades together would actually melt in the heat!

Since that time, EMS helicopters (and rotorcraft in general) have become much more robust, purpose-built, and mission-capable. So has the equipment used in HEMS missions. Among the most notable: “Night vision goggles that let pilots see in the dark,” says Cameron Curtis, president & CEO of the Association of Air Medical Services and Medevac Foundation International. “There’s also the ability to track helicopter positions accurately using satellites and GPS; enhanced communications between helicopters and the ground; and collecting flight data for daily operational analysis.”

“The safety and reliability of rotorcraft technology that we have achieved over the years is paramount,” agrees Lockheed Martin Rotary & Mission Systems Communications Product Marketing Manager David Franc. “Safety-enhancing systems such as advanced autopilots, single and dual pilot IFR capabilities, enhanced ground proximity warning systems (EGPWS) and night vision goggle (NVG) compatibility are just some of the tools to aid the HEMS pilot in reducing their workload and increasing their situational awareness.”

Advances in helicopter design, engineering, and production have also contributed to the reliability of modern turbine engines, transmissions and airframes. “One of the best examples of how this technology has helped HEMS is with one of our children’s hospitals, where a 24-week premature baby was delivered and in need of hospitalization,” says Jeanette Eaton, vice president of Sikorsky Commercial Strategy & Business Development. “The crew knew if they placed the baby in a ground ambulance or airplane, the vibrations could burst the brain vessels in the baby’s head. So they chose the Sikorsky S76D with active vibration control, which completed the mission without incident.”

These advances, plus autopilots, crash resistant fuel systems, flight data monitoring systems, and the adoption of formal safety management systems (SMS), have made HEMS flights today safer and more reliable than ever before. “At one point, nearly 70% of all HEMS accidents were related to visual degradation, including entering IIMC and suffering from spatial disorientation,” says Tom L. Baldwin, GMR’s vice president of safety. Thanks to technological and training advances, this is no longer the case.

As for the future? The day could come when unmanned aerial systems (UAS) play a role in HEMS. “To what extent is unclear,” Baldwin says. “However, there are responses such as organ procurement that seem to hold promise.”

What is certain is that helicopters will continue to play a critical role in EMS response. Since that 1943 HEMS mission in Burma, there has been no substitute for this transport technology.