|

Sep

28

2020

|

|

Posted 5 years 160 days ago ago by Admin

|

|

There are wildfires in the woods, and then there are crazy-strange wildfires such as a recent one in Florida that was fueled by hundreds of cars. When you battle that kind of conflagration, you’re bound to learn a few new lessons. We certainly did.

For a bit of background, Charlotte County, Florida, is located south of Tampa and north of Fort Myers along the coast. It boasts the second-largest estuary in Florida (behind Tampa Bay) and is home to some of the best sport fishing in the world. The county is split into two unique environments. The eastern portion is sparsely populated, and 80,772 acres of it is home to Florida’s oldest wildlife management area that is used for recreational activities such as hunting and camping. Port Charlotte and Punta Gorda offer all the amenities of the bigger cities. The western portion of the county features the harbor, beaches and boating community of Englewood. These diverse environments require the county’s sheriff’s office aviation unit to be just as diverse in the missions it performs.

The aviation unit was established in 1996 with government surplus UH-1s and OH-58s. Like most counties in Florida, the unit originally was split into two parts, the sheriff’s office and mosquito control. Mosquito control would use the Hueys and the sheriff’s office would use the OH-58s.

The two parts have since merged into the sheriff’s aviation unit that provides all public safety and public health aviation to the county. It operates AS350s and UH-1s as multi-mission platforms; their missions include law enforcement, long-line rescue, mosquito control, and firefighting. By combining into one unit, the county was able to share resources and offer more services at a lower cost. The unit staffing is two sworn pilots, two A&P mechanics, and seven part-time tactical flight officers.

The aviation unit is called upon to provide mutual aid to the surrounding counties that don’t own aerial assets, and most of these requests come in the form of aerial firefighting. The Charlotte County aviation unit is uniquely capable in this task with a UH-1 Huey fitted with a 350-gallon fire tank, along with a 144-gallon Bambi Bucket for the AStars (AS350s).

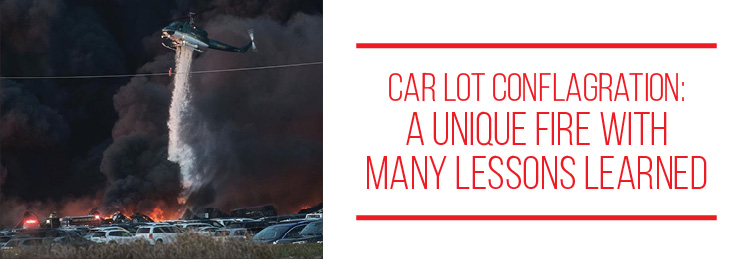

Our aviation unit recently provided mutual aid support on a unique fire at the Southwest Florida International Airport. A vehicle fire in the rental car lot had spread to hundreds of cars, creating a brushfire-like situation with vehicles. When Charlotte County’s UH-1 arrived on-scene, a Florida Forest Service helicopter was already there and welcomed the help of an additional firefighting asset. The fire was moving much like a traditional brushfire, however the thick toxic smoke obscured vision more than usual, and the fire was sustaining even with multiple drops of 350 gallons. There were traditional brushfire ground operations like dozers cutting fire lines, but in this case the fire lines were cut into rows of vehicles and the dozers were not traditional firefighting dozers used by the forest service; they were non-tracked construction dozers.

It quickly became obvious this was a unique kind of fire. Water had little effect on the fully involved vehicles. The dozers were creating mountains of exploding and burning vehicles on which water drops had no effect. Traditional fire engines and brush trucks were having trouble making their way through the maze of vehicles that were being repositioned out of danger by the rental car company.

Flying the Charlotte County helicopter, I focused water drops on the perimeter of the vehicle fires, effectively stopping the spread when the fully engulfed vehicles started to explode. I had experienced exploding vehicles under my helicopter as an OH-58D pilot in Iraq and Afghanistan. Based on this experience, I was able to keep the helicopter at a safe altitude while staying effective with the water drops.

Good communication with the Florida Forest Service helicopter was key to a successful multi-agency, multi-aircraft operation. The Charlotte County Sheriff’s Office and the Florida Forest Service had worked together on many occasions on the ground and in the air, so deconfliction and communication came easy. When the sheriff’s office helicopter deploys to a fire, its ground crew led by Lead Aviation Mechanic and Crew Chief Dan Ijpkemeule deploys as well with two fully equipped ground support personnel and 100 gallons of Jet-A.

Ground personnel are equipped with a 4X4 maintenance vehicle equipped with emergency lights, flash lights, night vision, field maintenance kit, and aviation and agency radios. They are trained to coordinate with local law enforcement and fire agencies to build landing zones, refuel helicopters, and provide air space and water dip site security/surveillance for NVG operations.

This fire burned well into the dark hours. The ground crew and I used NVGs to continue to provide safe, effective firefighting after all other aerial assets had gone home due to the loss of daylight. Intense fire degrades the functionality of NVGs, however techniques learned in Iraq and Afghanistan mitigated the risk of NVG washout created by the bright light of the fire. Night vision goggles for ground support personnel were essential. Without night vision, they could not provide a secure dip site or tell me when the tank was full of water. Night vision is used for distance viewing, and the mirrors are used to confirm a full firefighting tank is too close to use NVGs and too dark for the naked eye. The night vision used by the ground crew allowed them to inform me when the tank was full, and allowed me to remain focused on tasks.

#1. Training — Training doesn’t always have to be expensive and take a lot of time. It can be as simple as running through scenarios with your team. This allowed us to adapt to a complex and unique fire safely and effectively. Each member should know how to properly use their equipment, and initial and continuation training should be provided. Training with community partners created a great relationship with Charlotte County’s fire department, so it was easy to pick up a phone and request an asset or develop a new tactic, technique or procedure.

#2. Develop core missions — There is not an endless supply of money, so develop your core missions based on your community’s needs. For us, the broad picture was public safety and public health that developed into our core missions of law enforcement, firefighting, overwater rescue, and mosquito control to fit the community we serve.

#3. Conduct only those missions you are trained and equipped to do — You must understand that some missions will be outside the aircraft’s capabilities, and some will be beyond the pilot’s ability. It takes experienced, well-trained crews to complete complex missions.

#4. Always strive to do all that your aircraft and aircrews are capable of doing — If you provide a cost-effective solution, your agency may be more receptive than you may think. This may not happen overnight, but you need to be ready when the opportunity presents itself. Take advantage of teaming with other county agencies, and don’t forget to use the grants that are available to you. Our firefighting tank was selected because it is a dual-purpose tank that can conduct mosquito control and firefighting operations, and we teamed with the fire department to secure a Firehouse Subs grant that equipped our AStar with a hook. Our AStar works almost as many fires as our Huey.

#5. Always conduct after-action reviews (AARs) — It is easier to remember all the details when the event is fresh in your mind. The AAR from this fire brought several items to light that need improvement:

-

If you can use foam on a fire, do it. Since this fire, we have developed a foam injection system for our fire tank, making our drops five times more effective.

-

We have identified the need for two boxes of red chem sticks to easily mark obstacles; red is used because it is the most visible color under NVGs.

-

Ground crew uniforms need reflective material or reflective vests due to the high number of vehicles moving on-scene.

-

Develop a relocation plan if the fire gets too close to the refueling spot; this should be briefed on arrival.

-

Bring water, snacks, bug spray, and window-washing supplies because ash, smoke and water will quickly turn to mud and obstruct vision, especially while using night vision.

-

Have a ground support checklist. Just like the aircraft, the ground support personnel should have a checklist for deploying to a scene.

-

If possible, install a radio in the ground support vehicle to ensure you are not reliant on battery power. Have a way for the aircrew to directly communicate with the ground crew without interfering with fire radio channels. This can be as simple as a handheld air-band radio for the ground crew.

-

A handheld air-band radio has the added benefit of being able to communicate with the crews without the need of a repeater. This particular fire was out of our county, and our normal channels were unavailable because we were outside of our repeater’s range.

-

Take the ground crew up to verify dip sites before dark. This eliminates any miscommunication and verifies any hazards.

With these takeaways, the Charlotte County Sheriff’s Office Aviation Unit will be even more prepared to safely serve its community when called upon for its next mission, and we hope your aviation unit learns from our experience.

About the author: Shane is an 8-year veteran of the U.S. Army with deployments to OIF and OEF as an OH-58D scout pilot/instructor. After leaving active service, he was a primary flight instructor at Ft. Rucker, the home of Army Aviation. Shane then moved to the U.S. State Department where he served as a UH-1HII air mission commander for the International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Bureau. He then transitioned to the counter narcotics global support team where he served as an MI-17 instructor pilot. He also served as a lead pilot for an air ambulance company in New Mexico before becoming the chief pilot at the Charlotte County Sheriff’s Office, where he continues to serve his community.