NTSB Final Report: Cornwall, NY

|

Location:

|

Cornwall, New York

|

Accident Number:

|

ERA22FA010

|

|

Date & Time:

|

October 10, 2021, 13:57 Local

|

Registration:

|

N637HP

|

Aircraft: ROBINSON HELICOPTER COMPANY R44 II

Aircraft Damage: Destroyed

Defining Event: Loss of control in flight Injuries: 1 Fatal

Flight Conducted Under: Part 91: General aviation - Personal

Analysis

The non-instrument-rated helicopter pilot was returning to his home airport as the height of the overcast ceiling gradually decreased along the route of flight, consistent with the forecast conditions. While flying along the river valley at an altitude of 1,800 to 1,900 ft above mean sea level (100 to 200 ft below the clouds), the helicopter flew beneath an area of light-intensity precipitation echoes as detected by weather surveillance radar. It is likely that, at this time, the pilot encountered reduced visibility in very light rain and potential clouds. About the same time, the helicopter began to climb, and its groundspeed decreased. Shortly after climbing above the altitude of the reported cloud ceiling, the helicopter entered a relatively constant-rate turn.

About 9 seconds later, the track straightened for about 3 seconds, the climb rate plateaued at about 2,400 feet per minute, and the groundspeed began to increase. The helicopter continued to climb for another 10 seconds as the groundspeed increased to about 95 knots. During this time, it again turned toward the right for about 9 seconds. Just before the end of the turn, the helicopter began to descend rapidly. As it descended through the altitude of the cloud ceiling, the rate of descent reached 16,200 feet per minute. The tracking data ended about 2 seconds later in the vicinity of the accident site.

Postaccident examination of the airframe revealed no preimpact anomalies that would have precluded normal operation. Damage and fragmentation to the main and tail rotor blades, along with score marks on a frame tube near the tail rotor drive intermediate coupling, were consistent with rotor system rotation during the impact sequence. Impact marks found on the upper drive sheave and dents found on two of the engine’s cooling fan blades were consistent with the engine’s crankshaft not rotating at the time of impact. The drive sheave mark was an imprint with an outline of teeth from starter ring gear, which was mounted on the engine crankshaft. The imprint, (rather than scoring or cut grooves) was consistent with the engine’s crankshaft was not rotating when it contacted the sheave. Similarly, the dents on the cooling fan blades, each found directly below airframe components that likely caused the dents, suggest the cooling fan was not rotating when its blades made contact during impact. Also, the fuel servo mixture arm was found bent and in the idle-cutoff (no fuel to engine) position. The mixture cable sheathing was found stretched in several locations, consistent with tension. Tension on the cable, and other impact forces, likely pulled the mixture arm toward the idle- cutoff position. Despite these findings, no evidence of any preimpact mechanical malfunctions or failures of the engine were discovered that would have precluded normal engine operation. The flight track information, which showed a simultaneous climb and increase in groundspeed before the accident, was consistent with the engine providing power; therefore, it is likely that the crankshaft stopped during the impact sequence before the helicopter came to rest.

The pilot’s continued visual flight rules flight into an area of instrument meteorological conditions due to clouds and precipitation likely resulted in his loss of outside visual references, an environment conducive to the development of spatial disorientation, and the helicopter’s flight track was consistent with the known effects of spatial disorientation.

According to the pilot’s logbook, he had not received any instrument training, nor was the helicopter certified for flight in instrument conditions. These factors increased the likelihood of the pilot becoming spatially disoriented after encountering reduced visibility conditions.

Probable Cause and Findings

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The non-instrument-rated pilot’s continued flight into deteriorating weather conditions, which resulted in a loss of control due to spatial disorientation.

Findings

Personnel issues - Spatial disorientation - Pilot

Personnel issues - Aircraft control - Pilot

Environmental issues -Low ceiling - Ability to respond/compensate

Environmental issues - Rain - Ability to respond/compensate

Aircraft -(general) - Unknown/Not determined

|

Factual Information

History of Flight

Enroute-cruise - Loss of visual reference

Enroute-cruise - Abrupt maneuver

Enroute-cruise -Loss of control in flight (Defining event)

Uncontrolled descent - Collision with terr/obj (non-CFIT)

|

On October 10, 2021, at 1357 eastern daylight time, a Robinson R44 II, N637HP, was destroyed when it was involved in an accident in Cornwall, New York. The pilot was fatally injured. The helicopter was operated as a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 personal flight.

According to fueling records, the pilot purchased 24.6 gallons of fuel before his departure from Floyd Bennet Memorial Airport (GFL), Glenn Falls, New York. The flight departed about 1247 with a destination of MacArthur Airport (ISP), Ronkonkoma, New York, where the helicopter was based.

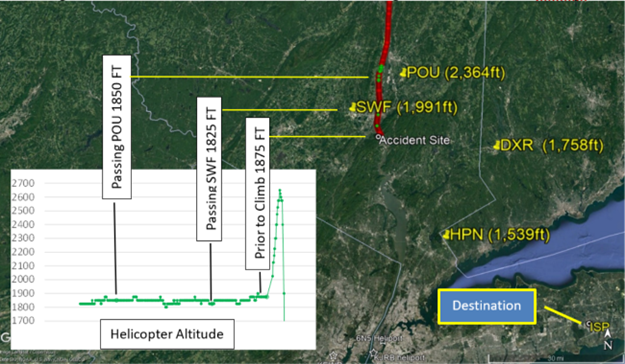

According to ADS-B tracking data and National Weather Service (NWS) records, as the helicopter flew south along the Hudson River at an altitude of 1,800 to 1,900 ft above mean sea level (msl), the overcast cloud ceiling height was decreasing. As it passed by Poughkeepsie, NY (POU) at 1349, the ceiling reported there was about 2,364 ft msl. At 1353, about 7 miles further south, the helicopter passed by the Stewart International Airport (SWF) where the ceiling was reported to be about 1,991 ft msl. At 1356, the helicopter began to climb (see figure 1).

Figure 1 – Helicopter’s ADS-B-derived flight track (red/green dots) and cloud heights at nearby airports (yellow text)

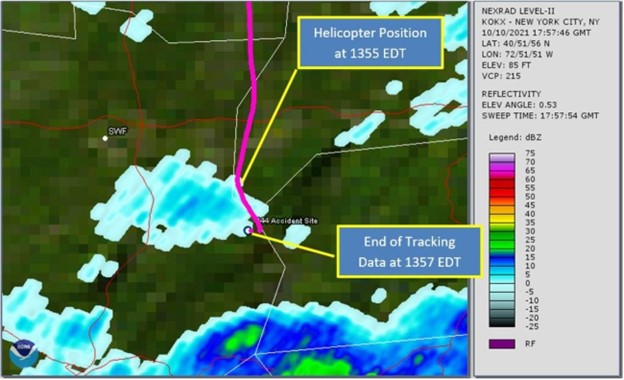

According to NWS weather surveillance radar data, near the time the climb began, the helicopter encountered an area of light intensity echoes that were moving to the north- northwest (see figure 2).

Figure 2 – Helicopter’s flight track (magenta) and weather radar base reflectivity at 1357

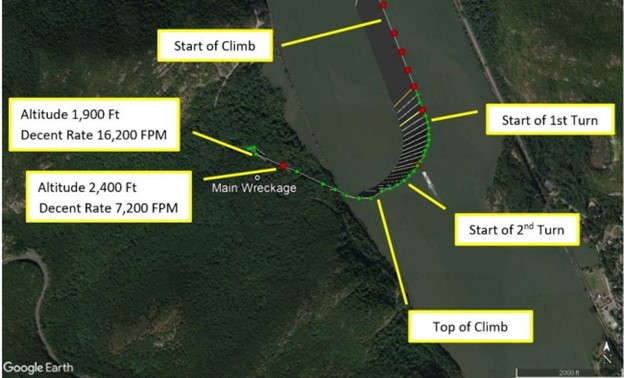

At 1356:03 while at an altitude of 1,875 ft msl, and a ground speed of 101 knots, the helicopter began to climb straight ahead. About 9 seconds later, it reached an altitude of 2,025 ft, which was above the cloud ceiling height reported at SWF (1,991 ft). About 5 seconds later it began the first of two right turns (see figure 3). The first turn lasted about 9 seconds, with an average turn rate of 7 to 11° per second.

Figure 3 – Helicopter’s flight track during climbing turn and subsequent descent (red and green dots)

From the start of the climb until about the end of the first right turn, the rate of climb continually increased, and the airspeed continually decreased. At the end of the first turn, the rate of climb plateaued at about 2,400 feet per minute, and the airspeed had decreased to about 45 knots. Just as the rate of climb plateaued, the airspeed trend reversed and began to increase. The helicopter continued to climb for about 10 seconds, as the airspeed increased to about 95 knots. During this time the second right turn began, lasted for about 9 seconds, at an average turn rate of 9-12° per second. At 1356:34, just before the end of the second turn, the helicopter began to descend rapidly from its peak altitude of 2,650 ft. About 6 seconds later, the descent rate reached 7,200 feet per minute. As it descended through 1,900 ft (just below the cloud ceiling height reported at SWF), the descent rate reached 16,200 feet per minute. The tracking data ended about 2 seconds later, about 0.6 nautical miles north of the accident site. The entire flight was about 70 minutes long and the accident site was located about 120 nautical miles south of GFL.

A witness on a hiking trail about 0.1 mile southeast of the accident site reported hearing the helicopter’s engine “falter and die.” One to two seconds later, he heard a swishing sound, which he attributed to the helicopter “spinning” or being “out of control;” however, he could not see the helicopter due to the tree canopy. Shortly thereafter, he heard a series of loud noises that he described as “backfires, at machine gun speed” for about 2 seconds, which he surmised was “the engine catching and the rotors slapping,” and then the sounds stopped. He reported that the visibility was “clear,” and the clouds were higher than the mountain peaks; there was no fog over the river, and he could see the river clearly from his location on the hiking trail.

A second witness located about 1/2-mile northwest of the accident site reported hearing a “loud noise” that he believed was the helicopter’s engine. When he turned toward the noise, he observed the helicopter in a nose-down attitude of nearly 90°, travelling at a “high speed…straight down.” The witness lost sight of the helicopter as it descended below a tree line; shortly thereafter, he “heard it crash.” The noise he associated with the helicopter’s engine was continuous until the sound of impact.

Pilot Information

|

Certificate:

|

Private

|

Age:

|

73,Male

|

|

Airplane Rating(s):

|

None

|

Seat Occupied:

|

Right

|

|

Other Aircraft Rating(s):

|

Helicopter

|

Restraint Used:

|

Unknown

|

|

Instrument Rating(s):

|

None

|

Second Pilot Present:

|

No

|

|

Instructor Rating(s):

|

None

|

Toxicology Performed:

|

Yes

|

|

Medical Certification:

|

Class 3 Without waivers/limitations

|

Last FAA Medical Exam:

|

June 23, 2020

|

|

Occupational Pilot:

|

No

|

Last Flight Review or Equivalent:

|

September 3, 2021

|

|

Flight Time:

|

504 hours (Total, all aircraft), 473 hours (Total, this make and model), 290 hours (Pilot In Command, all aircraft), 23 hours (Last 90 days, all aircraft), 4 hours (Last 30 days, all aircraft), 0 hours (Last 24 hours, all aircraft)

|

The pilot held a private pilot certificate with rotorcraft-helicopter rating. He did not have an instrument rating. A review of his logbook revealed that he had not recorded any actual or simulated instrument flight experience, and no instrument training was noted in the remarks section of any log entries. In November 2020, one flight was remarked with “IFR Conditions, asked for special VFR.” In May of 2021, one flight was remarked with “low clouds, rain, autopilot through clouds.”

Aircraft and Owner/Operator Information

|

Aircraft Make:

|

ROBINSON HELICOPTER COMPANY

|

Registration:

|

N637HP

|

|

Model/Series:

|

R44 II

|

Aircraft Category:

|

Helicopter

|

|

Year of Manufacture:

|

2007

|

Amateur Built:

|

|

|

Airworthiness Certificate:

|

Normal

|

Serial Number:

|

11942

|

|

Landing Gear Type:

|

Skid

|

Seats:

|

4

|

|

Date/Type of Last Inspection:

|

March 2, 2021 Annual

|

Certified Max Gross Wt.:

|

2500 lbs

|

|

Time Since Last Inspection:

|

77 Hrs

|

Engines:

|

1 Reciprocating

|

|

Airframe Total Time:

|

867 Hrs at time of accident

|

Engine Manufacturer:

|

Lycoming

|

|

ELT:

|

C91 installed, activated, did not aid in locating accident

|

Engine Model/Series:

|

IO-540-AE1A5

|

|

Registered Owner:

|

On file

|

Rated Power:

|

245 Horsepower

|

|

Operator:

|

On file

|

Operating Certificate(s) Held:

|

None

|

The helicopter was equipped with inflatable landing gear floats and a flight control stability augmentation system.

Meteorological Information and Flight Plan

|

Conditions at Accident Site:

|

Visual (VMC)

|

Condition of Light:

|

Day

|

|

Observation Facility, Elevation:

|

SWF,491 ft msl

|

Distance from Accident Site:

|

7 Nautical Miles

|

|

Observation Time:

|

13:45 Local

|

Direction from Accident Site:

|

310°

|

|

Lowest Cloud Condition:

|

|

Visibility

|

5 miles

|

|

Lowest Ceiling:

|

Overcast / 1500 ft AGL

|

Visibility (RVR):

|

|

|

Wind Speed/Gusts:

|

5 knots /

|

Turbulence Type Forecast/Actual:

|

None / None

|

|

Wind Direction:

|

70°

|

Turbulence Severity Forecast/Actual:

|

N/A / N/A

|

|

Altimeter Setting:

|

30.2 inches Hg

|

Temperature/Dew Point:

|

16°C / 14°C

|

|

Precipitation and Obscuration:

|

Moderate - None - Mist

|

|

|

|

Departure Point:

|

Glenn Falls, NY (GFL)

|

Type of Flight Plan Filed:

|

None

|

|

Destination:

|

Ronkonkoma, NY (ISP)

|

Type of Clearance:

|

None

|

|

Departure Time:

|

12:47 Local

|

Type of Airspace:

|

Class G

|

Weather conditions reported at the nearest reporting station (SWF) at the time of the accident included wind from 070° at 5 knots, visibility 5 miles in mist, ceiling overcast at 1,500 ft agl, (1,991 ft msl, based on the station’s elevation), temperature 16° C, dew point temperature 14° C, altimeter setting 30.20 inches of mercury. Data from other reporting stations along the route of flight near the accident and toward the destination airport indicated that overcast ceiling heights were decreasing from north to south. Infrared satellite imagery depicted a thick layer of clouds that obscured the accident site, with cloud tops near 27,000 ft. Weather surveillance radar imagery depicted a small area of light echoes near the end of the ADS-B data, and a large area of light to moderate echoes between the accident site and the intended destination (ISP). The radar’s lowest scanning beam was centered about 5,800 ft msl over the accident site.

The Terminal Aerodrome Forecast (TAF) issued at 0723 expected marginal visual flight rules conditions to prevail at SWF, with visibility of 6 statute miles or greater and overcast cloud ceilings at 1,200 ft above ground level (agl). The next closest TAF, also issued at 0723, expected instrument flight rules (IFR) conditions to prevail at Westchester County Airport (HPN), White Plains, New York (located 25 nautical miles southeast of the accident site), with visibility 5 statute miles in light rain showers, and cloud ceiling overcast at 800 ft agl.

A national weather service AIRMET Sierra, current at the time of the accident, advised of IFR conditions expected due to ceilings below 1,000 ft agl and/or and visibility below 3 miles in precipitation and mist. The AIRMET extended over the accident site and the planned destination. There were no other SIGMETs, convective SIGMETs, or CWA’s current for the area during the period surrounding the flight.

A search of the FAA contract Automated Flight Service Station provider Leidos indicated that they, and no other 3rd party vendors utilizing the Lockheed Flight Service (LFS) System, had any contact with the pilot of the accident helicopter on the day of the accident. A separate search of ForeFlight records indicated that the pilot had an account with the vendor and had used the application at 1113, and that he had created a route string for a flight from ISP to GFL via the Hudson River and back to ISP at an altitude of 1,000 ft. Before the flight, the following airports were viewed in the application (which includes the latest METAR, TAFs, and NOTAMs): Brookhaven Airport (HGV), Shirly, New York, and Minute Man Air Field (6B6), Stow, Massachusetts. The pilot did not view any weather imagery inside the application. No formal route briefing was requested and there was no confirmation the pilot reviewed or searched for the current inflight weather advisories for the area. The pilot had multiple tablet devices in the cockpit, all of which were too damaged to examine after the accident.

Wreckage and Impact Information

|

Crew Injuries:

|

1 Fatal

|

Aircraft Damage:

|

Destroyed

|

|

Passenger Injuries:

|

|

Aircraft Fire:

|

None

|

|

Ground Injuries:

|

N/A

|

Aircraft Explosion:

|

None

|

|

Total Injuries:

|

1 Fatal

|

Latitude, Longitude:

|

41.42726,-73.98556

|

Examination of the accident scene revealed a debris path that was about 110 ft-long and oriented on a heading of about 168° magnetic. It began with damaged treetops and broken limbs, where the tail rotor assembly and fragments of the tail rotor guard were located. The tail rotor blades were largely intact with leading edge gouge damage. The main impact crater, which contained fragmented landing gear components, was about 60 ft from the damaged tree, with the main wreckage located about 60 ft beyond the impact crater. The fuselage was fragmented and compressed from the nose toward the rear seats.

Flight control continuity could not be confirmed due to impact damage and some system portions were not located. However, all flight control attachment fittings remained attached at their ends. Most of the flight control push-pull tubes were fractured, some in multiple locations, consistent with overload.

The overriding clutch operated normally and smoothly when rotated by hand. The upper drive sheave had impact marks on the front and rear faces adjacent to the clutch centering strut and fuselage frame tubes, respectively. A 3-inch imprint consistent with the starter ring gear was present in the grooves of the upper sheave. The main and auxiliary fuel tanks were impact damaged; their bladders were breached, and a trace amount of fuel remained in the bladders. Some vegetation surrounding the impact crater and the main wreckage showed evidence of fuel blight. A portion of each main rotor blade (about 4 to 6 ft) remained attached to the hub.

Most of the spar of one blade also remained attached. Fragments of damaged main rotor blades were found along the debris path; the outboard 3 ft of one blade was found 273 ft northwest of the main wreckage. Some fragments were found with wood debris in the leading edge, others with chordwise streaks of brown residue on the surface consistent with tree material. Score marks oriented in the direction of rotation were found on a fuselage frame tube adjacent to the tail rotor drive shaft intermediate coupling. The filament of the low rotor speed warning lamp on the cockpit instrument panel was found intact and demonstrated hot filament stretching.

The engine crankshaft rotated smoothly when turned by hand at the cooling fan. Crankshaft and valvetrain continuity were confirmed as the crankshaft was rotated. Two of the cooling fan blades had impact marks/dents that were inline with airframe components located directly above the blades.

Thumb suction and compression were attained on all six cylinders. A borescope examination of all cylinders revealed no internal damage or anomalies. Both magnetos were found separated from the engine. The left magneto was fractured in half and with the lower half not recovered. The right magneto’s upper case and capacitor were impact damaged but otherwise intact. It would not produce spark on any leads when tested as found. After replacing the damaged capacitor, it operated normally. The fuel servo was separated from the engine and partially fragmented. The mixture control arm was bent inward toward the servo and was found in the idle-cutoff position. The push-pull mixture cable was not attached to the control arm and the attachment hardware was not present. The cable sheath was found stretched (in tension) in several locations.

Medical and Pathological Information

The Office of the Medical Examiner, Orange County, New York, performed an autopsy on the pilot. The autopsy report indicated the cause of death was blunt impact injuries.

Toxicology testing of the pilot was performed at the FAA Forensic Sciences Laboratory. Tamsulosin was detected in liver and muscle. Tamsulosin (Flomax) is an alpha blocker used to treat prostate hypertrophy and is acceptable for FAA medical certification.

Additional Information

Spatial Disorientation

The FAA Civil Aeromedical Institute's publication, "Introduction to Aviation Physiology," defines spatial disorientation as a loss of proper bearings or a state of mental confusion as to position, location, or movement relative to the position of the earth. Factors contributing to spatial disorientation include changes in acceleration, flight in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), frequent transfer between visual meteorological conditions (VMC) and IMC, and unperceived changes in aircraft attitude.

The FAA's Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-3A) describes some hazards associated with flying when the ground or horizon are obscured. The handbook states, in part:

The vestibular sense (motion sensing by the inner ear) in particular tends to confuse the pilot. Because of inertia, the sensory areas of the inner ear cannot detect slight changes in the attitude of the airplane, nor can they accurately sense attitude changes that occur at a uniform rate over a period of time. On the other hand, false sensations are often generated; leading the pilot to believe the attitude of the airplane has changed when in fact, it has not. These false sensations result in the pilot experiencing spatial disorientation.

Additionally, according to the Physiology of Spatial Orientation – (StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, nih.gov) Spatial Disorientation is defined as:

When the pilot fails to sense correctly the position, motion, or attitude of his aircraft or of himself within the fixed coordinate system provided by the surface of the Earth and the gravitational vertical.

Preventing Similar Accidents

Reduced Visual References Require Vigilance (SA-020)

The Problem

About two-thirds of general aviation accidents that occur in reduced visibility weather conditions are fatal. The accidents can involve pilot spatial disorientation or controlled flight into terrain. Even in visual weather conditions, flights at night over areas with limited ground lighting (which provides few visual ground references) can be challenging.

What can you do?

- Obtain an official preflight weather briefing, and use all appropriate sources of weather information to make timely in-flight decisions. Other weather sources and in-cockpit weather equipment can supplement official information.

- Refuse to allow external pressures, such as the desire to save time or money or the fear of disappointing passengers, to influence you to attempt or continue a flight in conditions in which you are not comfortable.

- Be honest with yourself about your skill limitations. Plan ahead with cancellation or diversion alternatives. Brief passengers about the alternatives before the flight.

- Seek training to ensure that you are proficient and fully understand the features and limitations of the equipment in your aircraft, particularly how to use all features of the avionics, autopilot systems, and weather information resources.

- Don’t allow a situation to become dangerous before deciding to act. Be honest with air traffic controllers about your situation, and explain it to them if you need help.

- Remember that, when flying at night, even visual weather conditions can be challenging. Remote areas with limited ground lighting provide limited visual references cues for pilots, which can be disorienting or render rising terrain visually imperceptible. When planning a night VFR flight, use topographic references to familiarize yourself with surrounding terrain. Consider following instrument procedures if you are instrument rated or avoiding areas with limited ground lighting (such as remote or mountainous areas) if you are not.

- Manage distractions: Many accidents result when a pilot is distracted momentarily from the primary task of flying.

See https://www.ntsb.gov/Advocacy/safety-alerts/Documents/SA-020.pdf for additional resources.

The NTSB presents this information to prevent recurrence of similar accidents. Note that this should not be considered guidance from the regulator, nor does this supersede existing FAA Regulations (FARs).

Administrative Information

|

Investigator In Charge (IIC):

|

Brazy, Douglass

|

|

Additional Participating Persons:

|

Chez Fogel; FAA/FSDO; Teterboro, NJ

Mike Childers; Lycoming Engines; Williamsport, PA

Thom Webster; Robinson Helicopter Corporatiion; Torrence, CA

|

|

Original Publish Date:

|

December 20, 2023

|

|

Investigation Class:

|

Class 3

|

|

Note:

|

|

Investigation Docket:

|

https://data.ntsb.gov/Docket?ProjectID=104078

|

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is an independent federal agency charged by Congress with investigating every civil aviation accident in the United States and significant events in other modes of transportation— railroad, transit, highway, marine, pipeline, and commercial space. We determine the probable causes of the accidents and events we investigate, and issue safety recommendations aimed at preventing future occurrences. In addition, we conduct transportation safety research studies and offer information and other assistance to family members and survivors for each accident or event we investigate. We also serve as the appellate authority for enforcement actions involving aviation and mariner certificates issued by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and US Coast Guard, and we adjudicate appeals of civil penalty actions taken by the FAA.

The NTSB does not assign fault or blame for an accident or incident; rather, as specified by NTSB regulation, “accident/incident investigations are fact-finding proceedings with no formal issues and no adverse parties … and are not conducted for the purpose of determining the rights or liabilities of any person” (Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations section 831.4). Assignment of fault or legal liability is not relevant to the NTSB’s statutory mission to improve transportation safety by investigating accidents and incidents and issuing safety recommendations. In addition, statutory language prohibits the admission into evidence or use of any part of an NTSB report related to an accident in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report (Title 49 United States Code section 1154(b)). A factual report that may be admissible under 49 United States Code section 1154(b) is available here.

|

READ MORE ROTOR PRO: https://justhelicopters.com/Magazine

WATCH ROTOR PRO YOUTUBE CHANNEL: https://buff.ly/3Md0T3y

You can also find us on

Instagram - https://www.instagram.com/rotorpro1

Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/rotorpro1

Twitter - https://twitter.com/justhelicopters

LinkedIn - https://www.linkedin.com/company/rotorpro1